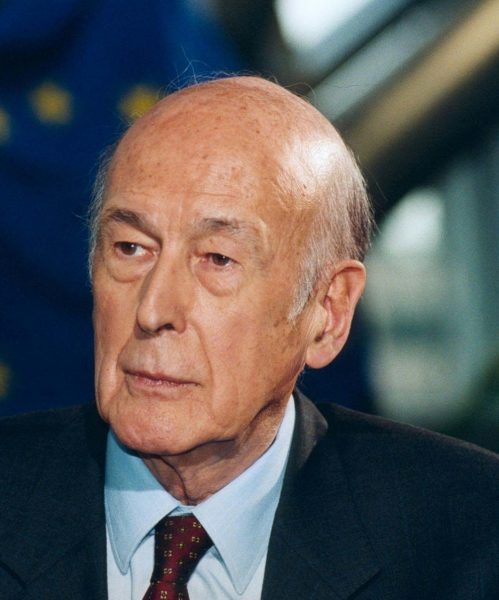

THE DOUBLE LIFE OF VALERY GISCARD D’ESTAING

What set Valéry Giscard d’Estaing apart as a political leader was his staying power: 40 years after he left office, it is historians, and not journalists, who are now assessing his achievements. Voices from all countries and across the political spectrum have paid tribute to the former French President’s contribution to European politics. It was his friendship and close understanding with Chancellor Helmut Schmidt that yielded the European Council, the election of Parliament by universal suffrage, and the European Monetary System, which paved the way for the single currency. That is already quite some legacy.

Yet much of what Mr Giscard d’Estaing did for Europe is often overlooked. You may not know it, but, once ousted from the Elysée, he led a second political life – one serving Europe. Firm in his belief that, from then on, it was Europe that would hold the reins on France’s future, he decided to become an MEP, placing himself in the Community’s engine room. As President of the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party, and later a member of the European People’s Party, he gave his support to the very first democratic campaigns in Berlin – when the effects of the wall, although razed, were still keenly felt – Poland and Hungary. Again with Helmut Schmidt, he lobbied tirelessly for monetary union in the run-up to the Maastricht Treaty, and remained unwavering in his commitment throughout the difficult ratification process and the painstaking preparations for its implementation.

But it was when chairing the 2002-2003 Convention on the Future of Europe that he really proved himself to be a great European, as he stepped into a role that

was commensurate with his ambitions for Europe. While his style had its detractors as well as its admirers, no one could deny that he was the man for the job. In stewarding the ship, he held his course, yet showed flexibility at the helm by looking to counsel from those he deemed ‘the young generation’s finest experts on Europe’. In the final weeks, with governments deeply divided over the Iraq war, he forged a seemingly impossible alliance between MEPs and national politicians that led to the approval of the first real draft constitutional treaty: consensus was reached among over 200 delegates, representing governments and large political parties from all EU Member States and candidate countries.

Alas, the glory was short-lived. The ‘no’ dealt to the constitutional treaty by the Dutch and French referenda delivered a painful personal setback on a par with his national defeat in 1981. And yet, as in 1981, he had made a considerable impact. A few years later, 95% of the text that had made up the draft constitution was repackaged as the Lisbon

Treaty. While important budgetary questions remained unanswered, the Treaty anchored the Union’s powers, put the institutions on a more stable footing, and established a democratic political architecture that drew on the federal parliamentary model in all but name. So, although it underwent a name-change before coming into force, the spirit of the ‘Giscard constitution’ will continue to inspire the Union for years to come.

A few weeks before his passing, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was still as driven as ever in his quest, overseeing the work of his new foundation – given the multilingual name ‘Re-imagine Europa’ – which aspires to invent the Europe of 2040. True greats never really die.

By Alain LAMASSOURE